The Little G Minor Fugue is based on this subject:

Tuesday, January 19, 2021

Bach - Fugue In G Minor (Little) BWV 578

The Little G Minor Fugue is based on this subject:

Sunday, October 18, 2020

Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 In G Major, BWV 1049

I. Allegro - The recorders play without the solo violin to a sparse downbeat accompaniment as the first movement begins. They play without the solo violin for a considerable amount of time before the soloist enters and the three instruments weave together. Later in the movement, the violin makes up for its silence in the beginning as it soars in virtuoso double stops, runs, and arpeggios. Based on this, this concerto could almost be considered a violin concerto. Bach's experiment with form and instrument uses makes for a hybrid form of concerto; a cross between a solo concerto and a concerto grosso.

II. Andante - The slow movement of this concerto is the only one of the set that has all the instruments participate. It is the recorders that contribute the most, as the solo violin is reduced to playing an accompaniment to them. The movement is in E minor, the relative minor of G major. The movement ends with an unresolved chord that leads to the last movement.

III. Presto - The final movement begins with a fugue played by the strings. The solo violin enters and ushers in the recorders as ideas are bounced back and forth by the soloists and strings in contrapuntal style.

This concerto was also converted to a concerto for harpsichord, recorders and strings, BWV 1057. It is interesting to note that many of Bach's harpsichord concertos were originally for violin. In this reworking, Bach transposes the music down to F major and gives the violin part of the original to the harpsichord.

The first video is the original Brandenburg Concerto No. 4. The second video is the arrangement Bach made of it, the Harpsichord Concerto No. 6.

Friday, September 18, 2020

Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 In F Major, BWV 1046

He had a wide reputation as the most knowledgeable musician concerning the organ. He earned extra money by traveling and assessing organs and what was needed to repair theme, as well as working as a consultant when new organs were being built. In the process, he would demonstrate by playing the organ in question, and as he was known as the best organist in the area, his reputation grew. He made contacts which aided him in his negotiation for future positions.

Bach also knew how to talk the talk of the era to royals. He sent the set of 6 concertos

(in his own handwriting) that are now called The Brandenburg Concertos to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt in 1721, while he was still employed by Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen. Bach had been hired by the Prince in 1717, and as the Prince was a lover of music, Bach did well there. But when the Prince got married in 1720 to a woman that didn't care for music, the importance of music in the court began to diminish. So Bach went job hunting, and along with the 6 concertos (a quite impressive resume), he sent along a dedication to the Margrave originally in French:

Since I had a few years ago, the good luck of being heard by Your Royal Highness, by virtue of his command, & that I observed then, that He took some pleasure in the small talents that Heaven gave me for Music, & that in taking leave of Your Royal Highness, He wished to make me the honor of ordering to send Him some pieces of my Composition: I therefore according to his very gracious orders, took the liberty of giving my very-humble respects to Your Royal Highness, by the present Concertos, which I have arranged for several Instruments; praying Him very-humbly to not want to judge their imperfection, according to the severity of fine and delicate taste, that everyone knows that He has for musical pieces...

It took two years from the time the Margrave ordered Bach to send him some compositions until they were sent, and they weren't specially composed for the Margrave. There is musicological evidence that shows the concertos had been written earlier. Whether Bach was honestly considered for the job or not is not known. What is known is that Bach took the job of Cantor in Leipzig in 1723, and stayed there the rest of his life. Whether the Margrave acknowledged the gift or had them performed isn't known.

There was no standardized orchestra in Bach's time. He would write for the instruments that were available to him. The instrumentation for this concerto is 3 oboes, bassoon, 2 horns (natural horns with no valves), violino piccolo, violin I and II, viola, cello, violone (double bass of the viol family of stringed instruments) and continuo. This is the only concerto of the set that is in 4 movements.

I. Allegro - This movement, along with the second movement was used in 1713. Bach rewrote the movement to include the violino piccolo. The movement begins with the hunting horns playing traditional hunting calls as the rest of the orchestra plays. Instruments take their turn in presenting themes while the horns punctuate the background with triplets. But the horns are more than an accompaniment; they have their time in the spotlight presenting themes as well, and never fade in the background much. One of the most distinguishing characteristics of this movement is the role the horns play in the ensemble, and even in the disruption of it.

II. Adagio - A solo oboe begins this movement, followed by the violino piccolo, a small violin that was tuned a minor third above a standard violin. These two instruments play off each other in a duet that is accompanied by the orchestra, minus horns. At the end, the falling notes of the bass alternate with the oboes and strings.

III. Allegro - The violino piccolo has solo material throughout this movement with a wonderful chugging rhythm in the bass. A distinctive touch is when the music comes to a slowdown with two bars of adagio tempo before the music resumes its original speed. Some musicologists believe this music first turned up in a previous cantata.

IV. Menuet - Trio, Menuet da capo: Polacca, Menuet da capo: Trio II, Menuet da capo - In writing technique, all the movements are in the mood of the concerto grosso, but in form they resemble the multiple orchestral suites of the time. The final movement is a graceful minuet, and after the trio for bassoon and oboes is done, a reprise of the menuet would usually end the movement. But Bach adds two more sections; a Polacca (Italian for Polonaise, a Polish dance) for strings, a reprise of the minuet, and a second trio for horns and oboes. One more reprise of the minuet brings the concerto to an end.

Monday, August 17, 2020

Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No. 5

Bach played for the Margrave, who enjoyed Bach's music. Bach offered to send some of his compositions to the Margrave upon his return to Cöthen. For various reasons (including the death of his wife) Bach put off sending anything to the Margrave until two years later. What prompted Bach to remember was the fact that Prince Leopold was engaged to a woman who did not care for music as much as the Prince did, and the rumor was that as soon as she was married she was going to use her influence on the Prince and have him disband his orchestra and release his musicians.

Bach played for the Margrave, who enjoyed Bach's music. Bach offered to send some of his compositions to the Margrave upon his return to Cöthen. For various reasons (including the death of his wife) Bach put off sending anything to the Margrave until two years later. What prompted Bach to remember was the fact that Prince Leopold was engaged to a woman who did not care for music as much as the Prince did, and the rumor was that as soon as she was married she was going to use her influence on the Prince and have him disband his orchestra and release his musicians. So Bach had six of his finest concertos bound together and he wrote a syrupy, pandering and overly-flattering dedication in French to the Margrave. He was basically sucking up to the Margrave looking for a job. There's no evidence that the Margrave ever had them performed, musical historians doubt that the Margrave's court had enough fine musicians to play the concertos. As for Bach, he moved on to Leipzig and spent the rest of his life there.

The first movement sees the three soloist dialogue with each other, with the harpsichord gradually garnering more of the spotlight with its music becoming more and more complex and decorated. The harpsichord becomes more and more demanding until the rest of the instruments give in and turn silent while the harpsichord gives us one of the best examples of Bach's prowess and improvising skills at the keyboard. The second movement is a gentle song played by the soloists only. The third movement is a lively gigue that rounds out the work.

This concerto is one of the first examples of a keyboard instrument having a solo part that was originally written for it, which paved the way for the classical piano concertos of Mozart and others.

Saturday, August 15, 2020

Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 In B-flat Major BWV 1051

As human beings are creatures that tend to have a hard-wired necessity to categorize things, musical historians have followed this predilection by breaking down the long history of music into eras. This has been useful in helping not only musicians to perform a work in as authentic a manner as possible, but it has aided the listener in their understanding of the work. That is not to say that all music lovers need an exhaustive education in music history and performance practice, but a little insight on the time in which the composer lived and how music was performed in that era can lead to increased enjoyment.

As human beings are creatures that tend to have a hard-wired necessity to categorize things, musical historians have followed this predilection by breaking down the long history of music into eras. This has been useful in helping not only musicians to perform a work in as authentic a manner as possible, but it has aided the listener in their understanding of the work. That is not to say that all music lovers need an exhaustive education in music history and performance practice, but a little insight on the time in which the composer lived and how music was performed in that era can lead to increased enjoyment.Johann Sebastian Bach is a composer that falls into the Baroque era (late Baroque era to be precise), but he did compose some works in the new gallant style, for example the Six Sonatas For Violin And Harpsichord. That Bach was a master of the so-called old style is true, but he was far more than that. He was a culmination of the late Baroque, and within that culmination were the seeds of the newer style, a style he was well aware of and more than capable of composing in.

While Bach is not thought of as being an innovator, he was quite creative in every facet of music and composition. The art of instrumentation for many years was thought to have been quite primitive in Bach's time, but the opposite has been found to be the case. With a wide variety of instruments and timbres, the Baroque composers and Bach in particular took every advantage of the differences in musical instruments to create tonal color, nuance and expression. One of Bach's many experiments in instrumentation is the Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 In B-flat. The concerto is scored for two violas, two violas da gamba (already considered an old instrument when this concerto was written in 1721), one cello, one violone (bass fiddle) and harpsichord. No soprano instruments save for the upper register of the keyboard. The resulting tonal color in the hands of a lesser composer would perhaps have become too dull and monotonous, but Bach writes music of great beauty in a joyful bluish purple color. The concerto is in three movements:

I. No tempo designation - Usually played in allegro tempo, this music has the two violas playfully chasing each other in canon interspersed with dialogue for the other instruments. While the violas chase each other the accompaniment of short repeated notes give a sense of movement to the music while the alternating sections go through key changes that add interest. Bach was said to have enjoyed playing the viola, so perhaps he took special delight in this movement. The violas da gamba play an accompaniment throughout and add movement and color to the overall tone of the movement.

II. Adagio ma non tanto - The violas da gamba are silent in this movement as the violas play a melancholy aria in duet. The cello and continuo alternate accompanying and playing sections of the aria. The movement ends with a whole note chord that gives a sense of suspended movement.

III. Allegro - In the style of a gigue, the violas begin in unison and soon chase each other even faster than in the first movement. The violas da gamba add to the texture and tone color while the cello has a few things to say of its own. The music for violas keeps moving in alternate moderate and fast note values until it reaches a point when the beginning section of the movement is repeated until a full close is reached.

J.S. Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No.3

Each one of the Brandenburg Concertos is different from the other. Number 3 in G major is for 3 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos, harpsichord and double bass. The style of this concerto harks back to the concerto grosso style, that is when a small group of instruments (the concertino) within the ensemble pass musical material back and forth while the full orchestra (tutti) accompanies. Number 3 is unique in that the two groups are integrated into a whole. Bach makes but eleven instruments sound like much more because each group of three alternates between being the concertino and being part of the tutti.

The first and third movements of the concerto are written in ritornello form while the middle movement consists of a two chord cadence. Some performers play these two chords, others improvise a short cadenza, sometimes a movement from a different work of Bach's is used. Evidently there was no set rule on which route to take. Composers of the Baroque era left a lot to the performers discretion.

Friday, February 14, 2020

Bach - The Well-Tempered Clavier Book II, Nos. 19-24

Both books of The Well Tempered Clavier contain 24 preludes and 24 fugues. That's a total of 96 pieces in both books combined. There have been some live performances of the complete Book I or Book II, but none to my knowledge that had them both on the same program. That would be far too much of a good thing for anyone but a musical masochist.

Both books of The Well Tempered Clavier contain 24 preludes and 24 fugues. That's a total of 96 pieces in both books combined. There have been some live performances of the complete Book I or Book II, but none to my knowledge that had them both on the same program. That would be far too much of a good thing for anyone but a musical masochist.With the music of Bach, the listener is confronted by multi-levels of creativity. There is the visceral pleasure of hearing it, as Bach's counterpoint can be so smooth and flowing that one forgets about it. He is far from being pedantic, and knows how to write a good tune and not just fugue subjects, and he is well aquainted with music in the different styles of his era. And of course he was a master crasftsman of music, with evidence that abounds in the Well Tempered Clavier. The interlacing of voices and textures is fascinating. and there is something about the fugues that make sense, whether the listener knows anything theoretical about harmony or counterpoint.

But this is music of over 250 years ago. For me at least, too big of a chunk at one time makes my ears go a little numb and my brain to get overtaxed. With all that has happened in the art of music since the death of Bach, it's no wonder that many listeners have a limit to what they can absorb at one time. That is why I broke down The Well Tempered Clavier into six preludes and fugues in a post, and sometimes that still pushes the limits of the modern ear.

Prelude and Fugue No. 19 in A Major, BWV 864 - This prelude is essentially in three voices that flow together to form a quite satisfying piece. There are no cadences that stand out to disrupt the calm atmosphere as a constant pulse of eighth notes continues to the end.

Prelude and Fugue No. 20 in A Minor, BWV 865 - The prelude begins with short notes in the right hand played over longer notes in the left, a feature that changes in the hands through the piece.This is a prelude that is in two voices. Sycopated eighth notes are sprinkled throughout the piece. The prelude is in two repeating sections, of similar length.

The abrupt two-measure subject consists of but 7 notes. But the accompanying material is not as much. as small note values make their way through the piece. Of interest is the final cadence which is in A minor, unlike the fugues in Book One (and some in Book II) that end with a Picardy third, that is a chord in the parallel major of the minor key.

Prelude and Fugue No. 21 in B-flat Major, BWV 866 - Another prelude in two sections with the second section longer than the first. The time signature of 12/16 hints at it being a gigue, a dance that is found at the end of a Baroque dance suite. The stylized dance forms were just that; many of them written by baroque composers were not meant to be danced to, any more than some of the stylized minuets of Haydn and Mozart. The obligatory repeats of this prelude make it one of the longer ones, and the mood is lively, if not in actual tempo then in feeling. There is a grand pause three lines from the end of the second section, after which each hand plays a 5-measure run of sixteenth notes with the final six bars summing up the section before the simple ending a B-flat an octave apart in eachhand.

The subject of the fugue is four bars long with the distinction of eigth notes being slurred in pairs in the 2nd and 3rd beat of the 3rd and 4th measure. A good performance of this fuge has these slurs repeated with every appearance of the subject.

Prelude and Fugue No. 22 in B-flat Minor, BWV 867 - The texture of this prelude is polyphonic, in three voices. It isn't obsessively slow in tempo as the movement of the voices need a certain amount of reined-in velocity. There are moments of major key sounds, and it ends in B-flat major.

With a subject more than 4 bars long and with two rests in its first two measures, this fugue takes some time to release the 4 voices. It winds its way with voices entering with repeats of the subject as well as other material, and the 4th bar from the end has all 4 voices speaking at once in eighth notes. The fugue ends in B-flat major.

Prelude and Fugue No. 23 in B Major, BWV 868 - A quite lively prelude that bristles with virtuoso toccata passages. It moves at a brisk pace with a steady rush of sixteenth notes, and ends before you know it.

A fugue with a four bar subject that is in marked contrast to the prelude. The tempo is more andante. Any slower and the fugue doesn't hold together very well. Bach's lack of tempo indications have given rise to all manner of interpretive suggestions by editors, some good and some not so much. The right tempo for a prelude and fugue has to be discoverred by the performer. A tempo that allows the accentuation of voices and textures first and foremost.

Prelude and Fugue No. 24 in B Minor, BWV 869 - A rarity with this prelude is a tempo designation given by Bach himself. The short notes within the prelude are written out ornaments, so Bach must have had certain definite ideas about this prelude. The prelude has the pieces of a sonata in form, and it ends in the minor.

This 3-voiced fugue has a subject 5 and a half measures long. There are many appearances of the subject as well as other non-subject material. The tempo can be fairly moderate, but the workings of the voice makes it seem like it goes faster. To round out the final fugue of the '48', Bach ends it with a Picardy third in B major.

Thursday, January 9, 2020

Bach - The Well-Tempered Clavier Book II, Nos. 13-18

Johann Sebastian Bach was an artist that was in many ways self-taught. He did have instruction from his family in clavier, violin, and organ, but he wasn't satisfied with just that. He wanted to know as much as he could about his art and craft, so he copied out music of other composers as well as traveled to hear masters play so he could learn from them. A case in point is the 250 mile journey he took on foot when he was 20 years old from Arnstadt to Lübeck to hear and learn from the famous (at the time) organist Dietrich Buxtehude. This wasn't the first time Bach had traveled a long distance. At the age of 15 he traveled from Ohrdruf to Lüneburg, a distance of 200 miles, to study at St. Michael’s School where he sang in the choir.

Johann Sebastian Bach was an artist that was in many ways self-taught. He did have instruction from his family in clavier, violin, and organ, but he wasn't satisfied with just that. He wanted to know as much as he could about his art and craft, so he copied out music of other composers as well as traveled to hear masters play so he could learn from them. A case in point is the 250 mile journey he took on foot when he was 20 years old from Arnstadt to Lübeck to hear and learn from the famous (at the time) organist Dietrich Buxtehude. This wasn't the first time Bach had traveled a long distance. At the age of 15 he traveled from Ohrdruf to Lüneburg, a distance of 200 miles, to study at St. Michael’s School where he sang in the choir.All of the travel, study and exposure to other musicians and music gave him an insight into the craft that made him a great performer, composer and teacher. Indeed, his duties at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, a position that he held from 1723 until his death, required that he supervise and provide the music for 4 churches in the community, play the organ as well as teach the choir and instrumentalists. Bach must have had a robust constitution most of his life, for he was a very busy man.

He taught his herd of children as well. some of them went on to make music their life and were very influential in their time. Johann Nikolaus Forkel wrote the first biography of Bach in 1802. Forkel knew some of his children, and C.P.E. Bach especially gave Forkel insight into the elder Bach's teaching methods. Forkel wrote:

To teach well a man needs to have a full mind. He must have discovered how to meet and have overcome the obstacles in his own path before he can be successful in teaching others how to avoid them. Bach united both qualities. Hence, as a teacher he was the most instructive, clear, and definite that has ever been. In every branch of his art he produced a band of pupils who followed in his footsteps, without, however, equaling his achievement. For months together he made them practice nothing but simple exercises for the fingers of both hands, at the same time emphasizing the need for clearness and distinctness. He kept them at these exercises for from six to twelve months, unless he found his pupils losing heart, in which case he so far met them as to write short studies which incorporated a particular exercise.The Well-Tempered Clavier was written with this in mind, as well as being an example of how a well-tempered tuning of keyboard instruments opened up the possibility of playing in all 24 major and minor keys. As Bach wrote in the preface to the work:

...for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning, and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study.Prelude and Fugue No. 13 in F-sharp Major, BWV 882 - A prelude of persistent dotted eighth note patterns. It is in 2 voices with the dotted note patterns appearing in almost every bar, usually in one voice or the other, seldom at the same time. The mood is maintained throughout until a few bars before the end when the music drifts into F-sharp minor. But this is momentary, and the prelude ends with a cadence to F-sharp major.

The subjects of Bach's fugues are like the seeds of plants. Some are simple, some are not, most of the subjects of his keyboard fugues are short, mainly because they were meant to be played on the non-sustaining keyboards of the harpsichord and clavichord. The fugues written for organ for the most part have longer subjects. The subject of this fugue is unusual in that it begins on the leading tone, that is the seventh note of the F-sharp major scale, instead of a note within the F-sharp major triad. This doesn't guide the ear to the key of the piece, but rather away from it. The music winds its way, but Bach brings it all to a satisfying conclusion.

The running sixteenth notes continue in this novel subject of 5 measures. This subject statement is heard only 6 times throughout, with the balance of the music taken up with counter subjects and episodes. In its liveliness, it is a perfect accompaniment to the prelude heard before it.

Prelude and Fugue No. 16 in G Minor, BWV 885 - This prelude is one of three in the entire set of 48 to have a tempo designation, Largo. Bach was adamant that this was not to be taken fast, but slow and stately.

Beginning on the second beat, the subject of this 4-voiced fugue has the 4th degree of the G minor scale (C) played out seven times at the end of it. As soon as the seventh C is sounded, the counter subject begins before the subject makes its second entry. The entry of the other two voices follows this pattern. The subject matter returns many times with changes in key, sometimes it plays against another version of the subject heard in a different voice. The music does end with a Picardy third (that is, with a major chord) but just barely. The final note of the fugue is a major third, B natural.

Prelude and Fugue No. 17 in A-flat Major, BWV 886 - A prelude of calm and sweetness of harmony. Although it is for the most part in two parts,s there are instances of chordal structures within it.

The subject of this 4-voiced fugue begins after an eighth rest and lasts for two measures. The seeming rhythmic simplicity hides the subtle syncopations within the piece.

Prelude and Fugue No. 18 in G-sharp Minor, BWV 887 - This prelude has unusual dynamic designations in it not normally found in the The Well-Tempered Clavier. In the third bar there is the term piano, while in the 5th measure there is marked forte. Perhaps this was meant for a harpsichord that could allow for different dynamics, or on the clavichord which was capable of slight variations in dynamics. The rest of the prelude is not so marked, but perhaps Bach did it to make the point that there were to be echo effects to be played in this prelude whenever the music demanded it and the instrument allowed it. There are two sections, almost of equal length; the second section has two more bars than the first. The prelude is mostly melody and accompaniment with little counterpoint involved.

The subject is 4 measures long, entirely in 8th notes, and the fugue looks remarkably plain on the printed page, but roughly half way through the fugue, Bach introduces a second subject that is more chromatic and of a different rhythm than the first. This helps the listener detect changes between the first half and the second half of the fugue, and helps avoid monotony. Each subject enters and leaves with differing voices, and aided by syncopation, they add variety. There are no increases of tension, no contrasts of major and minor. By the use of chromaticism and different motifs for each subject, as the subjects themselves, to create a mood of subtle color shifts.

Saturday, June 15, 2019

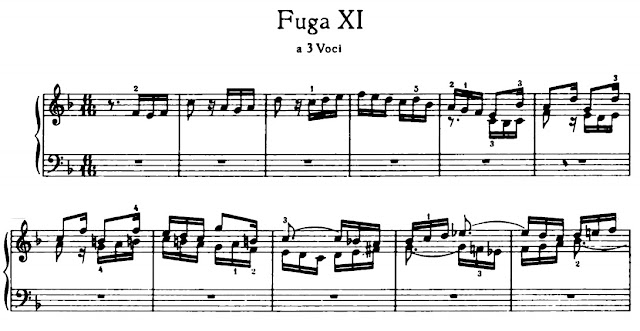

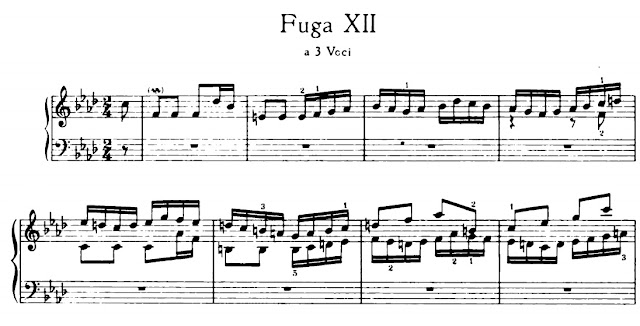

Bach - The Well-Tempered Clavier Book II, Nos. 7 -12

Bach intended Book II of The Well Tempered Clavier to fulfill the same uses as Book I; as a teaching aid for keyboard technique, theory and composition. But it also served as a showcase for him as a composer.While he was an acknowledged master of the compositional techniques of counterpoint (his works were called 'learned', not necessarily a compliment as used by some), he also knew the recent trends and the changes that were happening in musical styles.

Bach intended Book II of The Well Tempered Clavier to fulfill the same uses as Book I; as a teaching aid for keyboard technique, theory and composition. But it also served as a showcase for him as a composer.While he was an acknowledged master of the compositional techniques of counterpoint (his works were called 'learned', not necessarily a compliment as used by some), he also knew the recent trends and the changes that were happening in musical styles.Book II has more difficulties and is longer than Book I, and has not been as popular with players or listeners. But there are treasures to discover if one is willing.

Prelude and Fugue No. 7 In E-flat Major BWV 876 - This prelude has the feeling of flowing eighth notes throughout. It is not made up of themes, but consists of continuous movement that appears free from drama or overt tension.

The 4-voiced fugue begins with a subject that is repeated 12 times throughout.

Prelude and Fugue No. 8 In D-sharp Minor BWV 877 - The Prelude No. 8 in Book I was written in E-flat minor, while Fugue No. 8 of Book I was written in D-sharp minor, probably as a way for Bach to show the advantages of his well- tempered keyboard, as these 2 keys are theoretically different, but on the keyboard are only different in appearance on the music page. This Prelude/Fugue pair are written in the same key of D-sharp minor. As there was a separation of about 20 years between the composition of the books, the issue of which tuning to use may have been pretty much decided in the favor of well -temperament and Bach saw no need to emphasize it. Written in 2 voices, this prelude is similar to a 2-part invention, with its difference being in its length and complexity. The first 16 measures are to be repeated, as are the final 20 measures, thus the prelude is in binary form that is similar to what Bach used in some of the dance suites.

The 4-voiced fugue has a short two-measure subject that is repeated 16 times. There are a total of 8 episodes that are free of any subject

Prelude and Fugue No. 9 In E Major BWV 878 - This prelude moves along in 3 voices throughout, with the upper and middle voices contributing somewhat more thematic material than the lowest voice. It has two sections that are repeated.

The fugue that follows is in 4 voices. The subject consists of 5 notes with each voice entering directly after the preceding voice. There is no rush, as the fugue unfolds in a moderate tempo.

Prelude and Fugue No. 10 In E Minor BWV 879 - In two voices throughout, an extended two-part invention. The prelude has two sections which are repeated, with the second section being longer. Trills in one hand help to define that voice while the opposing voice has its say.

A 3-voiced fugue that has the subject begin with an upbeat of the 2nd and 3rd notes of a triplet. It is rather a long subject at six measures that covers an octave. Bach uses this theme to garner interest even before the fugal entry begin. This subject occurs nine times during the fugue with no changes to it. There are six episodes in the fugue that do not contain the subject within it. The pace of the fugue is not fast, but it does have movement to it by way of the staccatos and triplets.

Prelude and Fugue No. 11 In F Major BWV 880 - A prelude in a pastoral, calm mood that begs to be played legato with no accents. This prelude reminds me somewhat of the beginning of the Prelude No. 7 in E-flat BWV 852 of Book I.

The 3-voiced fugue is written in 6/16 time, a signature that shows the basic pulse is sixteenth note triplets, 2 triplets to the bar. The bouncing subject is stated 8 times during the fugue. Most of the fugue is taken up by the six episodes.

Prelude and Fugue No. 12 In F Minor BWV 881 - The prelude begins meditatively, but with shifts into the major, the prelude has an underlying energy that may lead to some performers performing it too fast. This is another prelude from Book II that is in binary form, and as Bach develops sections of this prelude, it shows that it was a form that lead to the development of sonata-allegro form with later composers.

The character of the 3-voiced fugue as well as its 2/4 time signature gives the opportunity to increase the tempo. The subject appears 9 times, with 6 subject-free episodes. Much of Bach's music derives from dance forms that were old in his time, and this fugue has a sway to it that shows that derivation.

Monday, June 11, 2018

Bach - The Well Tempered Clavier Book II, Nos. 1-6

In the court and church appointments that Johann Sebastian Bach had throughout his life, he was not only required to compose and lead the musicians in performance, but to teach them as well. He himself was taught the basics of music by his older brother after the death of his parents. But his innate curiosity lead him to copy out music of other composers to learn all he could. This was a common occurrence of the time as most music was not published and if it circulated at all it was in the form of hand-made copies. So Bach was probably an autodidact to a large degree.

In the court and church appointments that Johann Sebastian Bach had throughout his life, he was not only required to compose and lead the musicians in performance, but to teach them as well. He himself was taught the basics of music by his older brother after the death of his parents. But his innate curiosity lead him to copy out music of other composers to learn all he could. This was a common occurrence of the time as most music was not published and if it circulated at all it was in the form of hand-made copies. So Bach was probably an autodidact to a large degree.By copying and filtering the music of others through his mind, he created his own way of doing things, which in turn made him an excellent teacher.

The preludes and fugues of the Well Tempered Clavier were written and used to instruct and entertain students and musicians. Leave it to the creative urge of Bach to write not just one set of 24 preludes and fugues, but two. But the differences in the two books are evidence that Bach didn't repeat himself with the second set.

The second book of the Well Tempered Clavier appeared roughly twenty years after the first volume, and Bach surely did not remain static. His style broadened, he encompassed more of the current trends in composing. While it can be said that the first book is more obviously geared to instruction, the second book is not as clear cut.

Prelude and Fugue No. 1 In C Major, BWV 870 - As in the first prelude of Book I, this prelude emphasizes harmonic progressions. But within those progressions occur snippets of melodies and themes, examples of how Bach could weave harmony and counterpoint into very satisfying music that makes profound musical sense.

The 3-voice fugue that follows has a subject that is 4 bars long, with a rest in the middle of it. Next the mildly declamatory prelude that precedes it, the fugue has a little bit of rhythmic bounce.

Prelude and Fugue No. 2 In C Minor, BWV 871 - C minor has been a key of passion and drama to many composers, and Bach wrote a dramatic prelude/ toccata in C minor in the first book. This prelude is decidedly less so. Any drama it has isn't obvious, and it is almost entirely written in two parts.

At only 28 bars, this fugue is somewhat short on the page. The subject is but one measure long, and Bach works out the fugue in a simpler form.

Prelude and Fugue No. 3 In C-sharp Major, BWV 872 - The only music Bach wrote in the key of C-sharp major is contained within the Well Tempered Clavier. The prelude of the first book is a brilliant piece, while this one is more studied and introverted and sounds akin to the C major prelude in the first book. There is a shift from 4/4 time to 3/8 time near the end and the music becomes a short fugato.

This 3-voiced fugue has a subject of only 5 notes, with the second entry coming before the first statement of it is complete.

Prelude and Fugue No. 4 In C-sharp Minor, BWV 873 - There was not always a particular feeling or emotion Bach conveyed with specific keys, but the key of C-sharp minor seems to be one of them. As in the first book, this prelude has a feeling of sadness. It is written in 3 voices throughout.

The fugue is in contrast to the prelude. It is written in 12/16 time, a compound meter of 4/4 time that implies a quick tempo. There is an interesting chromatic section within it.

Prelude and Fugue No. 5 In D Major, BWV 874 - The prelude opens with a fanfare and proceeds like a dance from one of Bach's sets of dance pieces. The first section is repeated, rather like a Scarlatti sonata, and some have conjectured that Bach knew about the development of sonata form. The theme bounces around the voices, and is answered as it makes its way to the end.

The 4-voiced fugue is stately and refined.

Prelude and Fugue No.6 In D Minor, BWV 875 - Written in two parts, a brilliant companion piece to the D minor prelude of Book One.

An interesting subject with a chromatic section in the eighth notes, and a complex set of note values from sixteenth triplets, sixteenth notes, and eighth notes.